Executive Summary

This protocol provides a standardized framework for assessing the welfare of farmed rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). It serves farm personnel conducting routine welfare monitoring and other industry professionals, including certifiers, auditors, and buyers. This protocol is designed to align with the welfare monitoring and assessment requirements of key certifications, such as RSPCA Assured and Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC).

While this protocol was developed primarily for ongrowing rainbow trout in seawater, users can apply it to juveniles or trout reared in other production systems. Application in these contexts requires careful interpretation, as certain thresholds may not directly translate to different life stages and production systems. The Centre for Aquaculture Progress will publish protocols for juvenile rainbow trout in freshwater in 2026.

With global production exceeding 1 million tons in 2023, rainbow trout represent a major commercial aquaculture species. At this scale, producers require robust, standardized tools to maintain high welfare standards. Operational Welfare Indicators (OWIs) are scientifically validated practical indicators, including individual morphological indicators, group-based indicators, and environmental indicators, which provide the foundation for systematic on-farm welfare monitoring and assessment.

While practical guidance on OWIs has been developed for other species, such as the Laksvel protocol for Atlantic salmon, and valuable documentation on rainbow trout welfare has been published by Nofima and APROMAR, existing resources lack comprehensive, standardized, and threshold-based assessment across a wide range of indicators for rainbow trout producers. This protocol addresses that gap.

This protocol enables farm personnel to systematically monitor the welfare of their stock, identify potential issues early, and implement corrective actions. This proactive approach helps producers understand the relationship between welfare and production performance, resulting in reduced losses, improved regulatory compliance, strengthened consumer trust, and a stronger and more sustainable aquaculture industry.

Stakeholder feedback

The Centre for Aquaculture Progress will regularly update this protocol based on the latest scientific evidence and evolving operational practices to ensure this protocol remains as relevant and accurate for producers as possible.

The Centre for Aquaculture Progress welcomes feedback and comments from all interested stakeholders to ensure this protocol remains practical, scientifically sound, and commercially relevant. We particularly welcome:

- New scientific findings from researchers and academics;

- Practical insights and operational challenges from producers; and

- Requests or priorities from regulators and certification bodies for further alignment with their requirements.

Stakeholder input will directly inform future updates and ensure the guidance continues to meet industry needs.

To submit feedback or questions, please fill out this form, or alternatively contact info@centreforaquacultureprogress.org.

Introduction

Rainbow trout, like other teleost fish, are animals capable of experiencing pain and stress. Ensuring their welfare during production requires systematic monitoring through Operational Welfare Indicators (OWIs). The increasing focus on OWI implementation reflects shared priorities shared across the aquaculture value chain: from producers, certification bodies and seafood buyers, to consumers, governments, and NGOs. By improving welfare outcomes, producers simultaneously achieve better growth, survival, robustness, and production efficiency, while meeting regulatory requirements and evolving consumer expectations.

This protocol provides a standardized, systematic framework for real-world commercial use, built upon the strongest available scientific evidence to support both on-farm management and compliance with key certification requirements.

These guidelines were primarily developed for ongrowing rainbow trout in seawater. Users can apply this protocol to other life stages or production systems, though application in these contexts requires careful interpretation.

Defining fish welfare and Operational Welfare Indicators (OWIs)

Fish welfare

Animal welfare is a complex and multifaceted topic, with many definitions and conceptual frameworks. Several widely recognized approaches include:

-

Nature-based: Animal welfare is achieved when animals can express natural behaviors and use evolved adaptations in environments that meet their species' behavioral and habitat needs.

-

Feeling-based: Animal welfare depends on subjective emotional experiences, requiring freedom from negative states (e.g., pain, fear) while enabling positive experiences (e.g., comfort, pleasure).

-

Function-based: Animal welfare is determined by proper biological functioning, including good health, normal growth and development, and the absence of disease, injury, or physiological dysfunction.

-

Coping-based: Animal welfare reflects an individual's ability to cope with environmental challenges, where poor welfare occurs when adaptation mechanisms are overwhelmed or inadequate.

-

Affective balance: Animal welfare represents the cumulative balance of positive and negative experiences over time, where good welfare occurs when positive experiences outweigh negative ones.

These frameworks are recognized as complementary rather than competing perspectives. Modern integrated approaches, such as the Five Domains Model, synthesize these perspectives by assessing welfare across multiple dimensions:

- Domain 1 (Nutrition): Adequate food and water (function-based).

- Domain 2 (Physical Environment): Appropriate thermal, atmospheric, and spatial conditions (nature-based, function-based).

- Domain 3 (Health): Absence of disease, injury, and functional impairment (function-based).

- Domain 4 (Behavioral Interactions): Opportunities for species-typical behaviors, agency, and control (nature-based, coping-based).

- Domain 5 (Mental State): Overall affective experience integrating domains 1-4 (feeling-based, affective balance).

This multidimensional framework acknowledges that welfare encompasses biological functioning, behavioral expression, and subjective experience, with each domain contributing to the animal's overall quality of life.

While acknowledging the complexity of the term ‘welfare’, this document adopts the same definition used in the Laksvel protocol for Atlantic salmon: “quality of life as perceived by the fish itself.” This definition aligns with the feeling-based and affective balance perspectives by centering on the fish's subjective experience. However, because subjective experience cannot be directly measured, this protocol uses observable indicators across multiple welfare domains as proxies for internal states.

The protocol's indicators are organized to provide comprehensive assessment across these five welfare domains, acknowledging that no single indicator can capture the multifaceted nature of welfare.

Operational Welfare Indicators (OWIs)

Operational Welfare Indicators (OWIs) are standardized assessment tools designed for routine implementation in commercial aquaculture. Unlike some other proxy measures such as plasma cortisol concentrations that require laboratory analysis, OWIs enable practical on-farm assessment. These indicators are scientifically validated, practically feasible, and provide actionable data for evidence-based management decisions.

This document classifies OWIs into three categories:

- Individual-based indicators (animal-based outcome measures): These assess the physical condition of individual fish (including parameters such as fin condition and skin condition) through sampling. Individual-based indicators directly reflect how the fish have been affected by its environment and management, providing outcome measures of their welfare state.

- Group-based indicators (outcome measures): These assess collective patterns at the population level, including behavior and mortality rates.

- Environmental indicators (input measures): These assess the aquatic environment, including dissolved oxygen and temperature. Environmental indicators represent the conditions fish experience and are critical determinants of welfare, though they are inputs (what is provided) rather than direct outcomes (how fish are affected).

Relationship Between OWI Categories and Welfare Domains

The table below shows how the three OWI categories address the Five Domains of welfare:

| Welfare Domain |

Individual-Based Indicators |

Group-Based Indicators |

Environmental Indicators |

| 1. Nutrition |

Emaciation |

Feeding behavior |

Feed quality, delivery (not in current protocol) |

| 2. Physical Environment |

Morphological damage related to environment |

Swimming behavior |

Water quality, stocking density |

| 3. Health |

Morphological damage including those related to disease signs, deformities |

Mortality |

Water quality (disease risk factors) |

| 4. Behavioral Interactions |

Morphological damage from aggression, (particularly fin damage) |

Aberrant fish, aggressive behavior, feeding behavior, swimming behavior |

Stocking density, water flow/velocity |

| 5. Mental State |

Pain-related morphological damage (inferred) |

Aberrant behavior |

Environmental stressors (e.g. suboptimal water quality or high stocking densities) |

![][image1]

Limitations

While OWIs provide valuable welfare assessment capabilities, users should be aware of several important limitations:

-

Evidence base variability: The scientific foundation supporting individual indicators varies considerably. Some indicators are well-validated in ongrowing rainbow trout in seawater, while others rely on evidence from different salmonid species, alternative life stages, or laboratory studies that may not fully reflect commercial conditions. Users should interpret indicators with limited validation with greater caution. More information on specific indicators is provided in the section ‘Evidence Quality’ below.

-

Indicator interpretation challenges: Some indicators may interact with each other, producing compounding effects on welfare, that cannot be captured by siloed assessment of individual indicators.

-

Sampling limitations: Morphological assessments require the sampling of individuals, which may not accurately reflect the welfare status of the entire production group. In large-scale operations, localized welfare issues could be missed if sampling protocols are insufficient or if welfare problems are unevenly distributed throughout the population.

-

Assessor subjectivity: Many morphological indicators rely on visual scoring instead of detailed measurements. While this approach enables rapid assessment, it introduces inter-observer variability and requires standardized training protocols to maintain consistency across evaluators. In addition, because OWIs are developed and interpreted from a human perspective, there is an inherent anthropocentric bias that may not fully reflect the fish’s subjective experience.

-

Practical limitations: OWI protocols must be practical and flexible for implementation across different commercial settings, which inherently involves trade-offs with precision. Because most producers cannot monitor OWIs continuously, assessments are typically carried out at discrete time points, providing only snapshots of welfare. In addition, fish may physiologically adapt to chronic stress and appear outwardly normal, meaning that short-term observations can underestimate ongoing welfare issues.

-

Equipment dependency: Environmental monitoring capabilities depend on available sensor technologies and their placement. Producers with limited monitoring equipment may have reduced capacity to track key environmental parameters, potentially missing welfare-relevant changes in water quality or environmental conditions.

-

Assessment only: This protocol focuses on welfare assessment and does not provide recommendations for addressing identified welfare gaps. Producers should therefore ensure they have strong management plans in place that enable them to act upon identified welfare issues.

These limitations highlight the need for producers to routinely and systematically measure multiple indicators across different categories rather than focusing on single indicators or one-off assessments. In tandem, protocols such as this one must be regularly reviewed and updated to reflect emerging scientific evidence and evolving understanding of fish welfare.

Evidence Quality

To address the variability of the evidence base between indicators (for more information see the Limitations section) and to ensure transparency, the table below summarizes the level of supporting evidence for each indicator. The table provides three considerations for each indicator: welfare significance (the importance of the indicator for fish welfare), rainbow trout-specific evidence (the number of and strength of scientific studies specifically on rainbow trout), and threshold validation (how well-established the proposed scoring thresholds in this protocol are).

While some indicators are more strongly validated than others, producers are encouraged to measure as many indicators as practicable. Additionally, tracking correlations between indicators over time can strengthen understanding of how these indicators reflect welfare within production systems.

| Indicator |

Welfare significance |

Rainbow trout-specific evidence |

Threshold validation |

| Individual-based indicators |

|

|

|

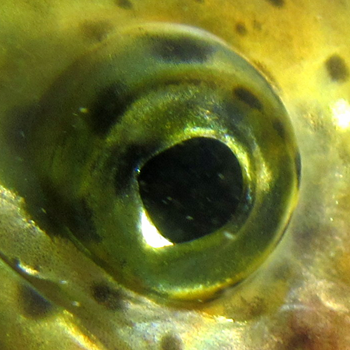

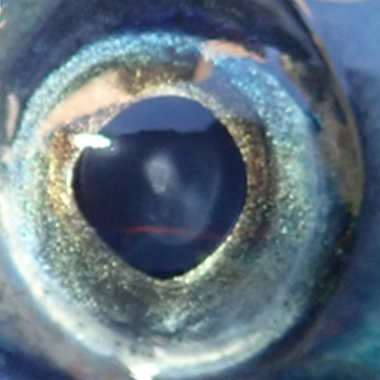

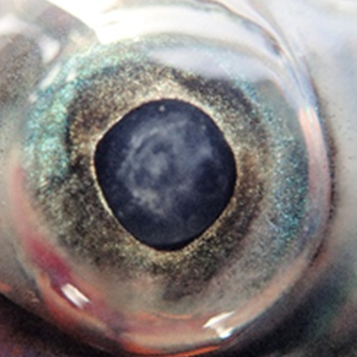

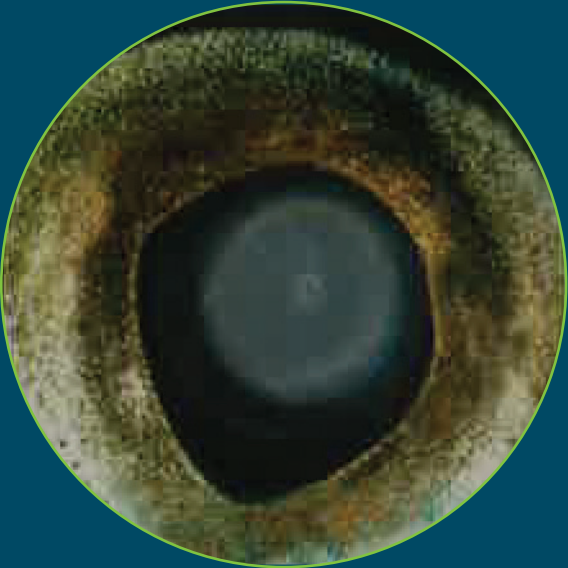

| Eye opacity |

High |

Moderate |

Low (extrapolated from salmon) |

| Eye injury |

High |

Very low |

Low (extrapolated from salmon) |

| Operculum damage |

Moderate |

Very low |

Low (extrapolated from salmon) |

| Gill damage |

High |

Very low |

Low (extrapolated from salmon) |

| Skin hemorrhaging |

Moderate |

Very low |

Low (extrapolated from salmon) |

| Scale loss |

Moderate |

Very low |

Low (extrapolated from salmon) |

| Wounds |

High |

Low |

Low (extrapolated from salmon) |

| Snout damage |

High |

Very low |

Low (extrapolated from salmon) |

| Fin damage |

Moderate |

High |

Moderate |

| Spinal deformity |

High |

Moderate |

Low (extrapolated from salmon) |

| Jaw deformity |

High |

Low |

Low (extrapolated from salmon) |

| Change of coloration |

Moderate |

Low |

Very low |

| Emaciation |

High |

High |

Moderate |

| Sea lice |

High |

Low |

Moderate (extrapolated from salmon) |

| Group-based indicators |

|

|

|

| Mortality |

High |

Moderate |

Low |

| Aberrant fish |

High |

Low |

Low |

| Aggressive behavior |

High |

Very low |

Very low |

| Feeding behavior |

High |

Low |

Low |

| Swimming behavior |

High |

Low |

Low |

| Environmental indicators |

|

|

|

| Stocking density |

High |

High |

Moderate |

| Dissolved oxygen |

High |

High |

High |

| Carbon dioxide |

High |

Low |

Very low |

| Temperature |

High |

High |

Moderate |

| Turbidity |

Moderate |

Low |

Very low |

| pH |

High |

Moderate |

Low |

| Total Suspended Solids |

Moderate |

Low |

Very low |

| Ammonia |

High |

Low |

Low |

| Nitrite |

Low |

Very low |

Very low |

| Nitrate |

Moderate |

Very low |

Very low |

| Metals |

High |

Low |

Very low |

| Water flow / velocity |

Moderate |

Low |

Low |

| Salinity |

High |

Very low |

Very low |

Method

OWI selection process

This protocol selected OWIs through comprehensive analysis of existing OWI frameworks and materials, a complete list of which is listed in the Appendix under ‘OWI Selection’.

The selection process involved:

- Systematic review of indicators used in established protocols (e.g. Laksvel for Atlantic salmon).

- Review of other materials considering operational welfare indicators, including those published by industry (e.g. Nofima’s ‘Welfare indicators for farmed rainbow trout: tools for assessing fish welfare).

- Analysis of certification requirements from major schemes (e.g. ASC, RSPCA Assured).

- Consideration of commercial need for the indicator to be included, scientific validity, practical feasibility, and welfare relevance for rainbow trout.

Threshold development process

Threshold recommendations for each OWI were developed through an indicator-specific systematic review of the current scientific literature, prioritizing evidence from ongrowing rainbow trout in commercial seawater conditions. Where such evidence was limited (which was often), the analysis incorporated evidence from different production systems, laboratory settings, alternative life stages, or other salmonids.

Each paper was evaluated based on the following criteria:

- Quality: Study design, sample size, peer review status, etc.

- Indicator Relevance: How directly the study investigated the impact of a specific indicator on welfare.

- Context: How closely the study context and findings apply to ongrowing rainbow trout in commercial seawater production, considering laboratory/commercial conditions, life stage, environmental conditions (e.g. stocking densities), and species.

Papers were graded as high, medium, or low, with findings weighted accordingly to inform final threshold recommendations for each indicator. This approach ensures the recommendations are grounded in the best available science while providing practical guidance where specific knowledge gaps exist.

Thresholds

Thresholds for each OWI are classified as ‘ideal’, ‘acceptable’, ‘warning’, and ‘unacceptable’. The 'acceptable', 'warning', and 'unacceptable' thresholds correspond to traffic light systems (green-yellow-red) commonly used in certification schemes. These levels should not be treated as linear in severity.

- Ideal: The indicator reflects a fully favorable state and supports a good quality of life.

- Acceptable: The indicator shows a mild deviation from the ideal, with minimal impact on welfare.

- Warning: The indicator reflects a moderate deviation from the ideal, presenting a risk to welfare if left unaddressed.

- Unacceptable: The indicator clearly compromises welfare, with a high likelihood of causing suffering or impaired function.

Thresholds for individual indicators describe the welfare impact on that individual fish; they do not prescribe target prevalence levels for the population.

Further guidance on assessing OWIs

Which indicators to assess and when

This protocol includes over 30 indicators. While having more data can be beneficial, monitoring all indicators may not be practical in commercial farm settings.

Producers should decide which indicators should be monitored at which frequencies, informed by their own site-specific experience, requirements by any certifications/regulators/customers, and practical constraints. These indicators should work together to provide a balanced picture of welfare.

Routine assessment enables early problem detection. Research in salmon found welfare scores changed within 2–3 month intervals, suggesting a higher frequency of monitoring is preferable. Certification schemes also provide guidance: For morphological assessments, ASC requires them to be conducted monthly; the Best Aquaculture Farm Standard recommends weekly checks; Naturland advises at least every 7 days during sensitive periods; and the RSPCA requires a minimum of four assessments in the freshwater stage and monthly in seawater.

At a minimum, behavioral indicators, mortality, dissolved oxygen and temperature should be monitored daily. Depending on the production system, other water quality indicators may also need to be monitored daily (e.g., ammonia in RAS systems). Morphological indicators should be assessed on a monthly basis at minimum. Since producers are already handling fish during sampling, it is strongly encouraged to assess all individual-based morphological indicators to maximize the data collected. If sampling occurs more frequently for other purposes (e.g., regulatory sea lice monitoring), morphological indicators should also be assessed during these events to use handling time efficiently.

Producers should increase monitoring frequency when specific risks are present (e.g. high temperatures, disease outbreaks, or after handling events), or when assessment results suggest emerging welfare problems. Alternatively, assessment frequency may be reduced over time if and only if consistent results and strong correlations are observed across certain time periods, indicating stable welfare conditions.

This protocol is deliberately granular to provide assessors with more detailed welfare data. Some indicators require assessment through more than one feature (e.g. structure and color for gills). In these cases, the overall score should be the most severe level.

However, certification requirements, internal company processes, or time constraints may require indicators to be grouped in their assessment. There also may be limited time to record each indicator separately, meaning that the number of indicators measured must be reduced.

In these cases, related indicators can be grouped into one score by:

- Assessing each indicator using the thresholds in the protocol; then

- Using the worst (most severe) score as the overall value for the grouped indicator.

For example:

- Combine “eye opacity” and “eye injury” into one overall “eye damage” score.

- Combine “skin hemorrhage,” “scale damage,” “wounds,” and “snout damage” into one overall “body surface damage” score.

- Combine “aberrant fish,” “aggressive behavior,” “feeding behavior,” and “swimming behavior” into one overall “behavior” score.

Grouping indicators reduces data granularity and may mask specific welfare issues. Group indicators only when necessary for compliance or practical constraints.

The Centre for Aquaculture Progress has developed separate guidance mapping each individual indicator in this document to specific certification requirements. This can be accessed at [INSERT LINK].

Sampling individual-based indicators

Methodological Notes

All indicators in this section are morphological individual-based outcome measures, meaning they require:

- Sampling of individual fish from the population;

- Scoring each sampled fish independently;

- Calculating prevalence (percentage of fish falling into each category of ‘ideal’, ‘acceptable’, ‘warning’, and ‘unacceptable’); and

- Using prevalence distributions to classify the population’s welfare status.

The process of sampling itself can be stressful for fish. Where possible, using observations from underwater camera systems (as long as they have been validated against traditional sampling assessments) is recommended.

Sample size

While classical sampling theory suggests that a sample of 30 is often sufficient regardless of population size, practical aquaculture conditions often violate key statistical assumptions:

- Spatial heterogeneity (fish not uniformly distributed)

- Catchability bias (healthy vs. sick fish differ in capture probability)

- Disease clustering (infections often spatially aggregated)

- Behavioral segregation (subordinate/sick fish may occupy different zones)

This means sampling 30 fish may not adequately represent welfare status across the entire population, particularly in large-scale operations. Therefore, we recommend scaling sample size with cage size:

| Cage size |

Recommended minimum sample |

| \< 20,000 |

30 |

| 20,000–100,000 |

50 |

| > 100000 |

100 |

The number of fish reasonably able to be sampled will depend on practical factors such as staff time and achieving the above minimums may not always be practical. Further, a post-mortem analysis of morphological indicators is recommended across a very large sample after harvest, as this does not involve further stress to the fish and can provide accurate prevalence data.

We recommend sampling each cage at the site. The number of cages assessed may be reduced over time if consistent results and strong correlations are observed across cages, and cages are assessed on a rotating basis.